In my previous article, I talk about what storytelling for design and innovation is, and why it works. Let’s look at examples of how people concretely use storytelling throughout the design process.

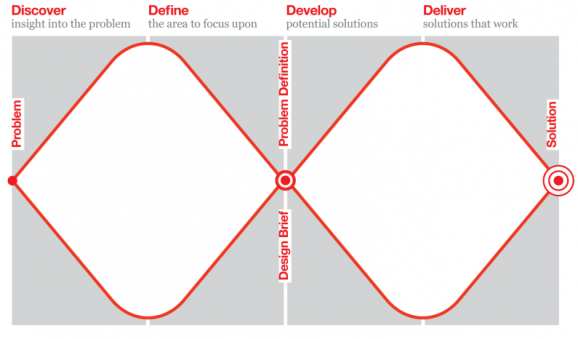

Although there are many models for the design cycle, I personally like the UK Design Council’s Double Diamond of Design.

Image Source: DesignCouncil.org.uk

The thinking is that in the first diamond, you open your thinking to discover the different dimensions of a problem, the narrow it down to an addressable design challenge, usually in the form of “how might we?”

You then re-open your thinking to ideate and develop potential solutions for the problem before narrowing it back down to a deliverable solution. If you’re a business program or initiative manager, you can also use this structure.

At a high level, designers try to bring informative stories INTO the discovery part of the design process, and inspirational stories OUT of the solution process to spark ideation, innovation and later on, adoption.

Let’s look at some examples how designers do this.

______

Phase 1: Discover

Informative stories on outliers…that become design principles

I feel like design is one big family and one designer in my network is Dominic Edmunds, a service design lead for leading global design and innovation agency Fjord in Berlin. He recounted a project he did for a financial services client.

Source: Fjord

“For one exercise, we removed a cover on the client group tables to reveal dozens of quotes from employees and customers for them to immerse in the voices of real people. In a follow up exercise, we created an ‘experience canvas.’ This was a massive board that had pockets filled with cards describing real life moments that we gathered during research.

“One of them was about a mortgage servicing manager who was struggling to foreclose on a property that was far past due on payments. Upon closer review, she discovered the house was occupied by a 90 year old widow. The service manager was stuck and unsure what to do.

“The story impacted the team. In the tightly measured world of debts and payments, this was a complete outlier that would have been just an annoying line on a status report.

“The team realized when employees and customers are relegated to rows in a database, we can lose sight of people.

“[The client’s] business is not about high performing loans, it’s about high performing people who feel empowered to own the mission.”

“We needed to reconnect staff with the impact they have on communities, clients and colleagues; thereby creating a deeper connection to the mission of the organization. This became a key design principle for internal operations, KPI representations, and external communications.”

Phase 2: Define

Informative stories about the unhappy path

Idea Couture is a leading business design agency, now part of Cognizant. I asked one of their founders who was then head of CX, Cheesan Chew, to tell me about an experience using storytelling.

Working with a global logistics player, her agency got the original design challenge of, “How might we get a package from point A to point B with as few problems as possible?” In other words, design an ideal happy path.

Creative business designers love this blank-page stuff. It’s pure innovation and design thinking. Come up with a brand new way for a physical good to move from one point to another? You can imagine the “innovation geek giggles” starting (“distributed 3D printing! Holograms! Teleportation!”)

Beginning with a global ethnographic research across 9 markets, they uncovered customer needs through contextual observation and organizational constraints via a deep analysis of the business and operations. After fieldwork, two critical insights emerged:

- The internal organizational view of the experience (as a process) was vastly different than the customer view (as a service).

- In shipping, customers expect problems – so don’t design for the happy path. Design for the unhappy path.

In hindsight, it’s completely logical. End-to-end logistics is one of the most complex services there is, along with air travel. With delayed and cancelled flights, mechanical failures, communication failures, traffic jams, misdirected packages, it is statistically impossible to have an idealized happy path. Of course it makes sense to focus on dealing with the real world rather than designing for a perfect one.

However, they needed to hear the stories of customers to hear about how these protagonists encountered a conflict (of expectations, promises, needs etc.) before they could focus on the resolution. To describe these “improved unhappy paths”, they created future state journey maps and user stories.

Informative stories that redefine your product

This example is not from an agency I personally know, but a case study from the International Journal of Innovation Science* that I found absolutely fantastic.

In the 1980s, consumer goods manufacturer Kimberly Clark fell behind its closest competitor in the category of baby nappies. They tried to promote superior product features (better absorption, zero leakage) but were stymied by the competition’s “boy & girl” nappies, which resonated better with the public.

After successive quarter-on-quarter declines, the VP of the business unit was fired and the new one was desperate to turn things around. He hired a design agency to look at product innovation.

After much research and countless customer interviews, they realised their thinking way off base.

They had always categorized nappies as a “non-emotional product” – they actually had used the term “waste control bandage.” But guess what: parents, and especially kids, had very emotional experiences with them! Parents told them stories about how nappies were clothing for their kids that they didn’t like very much (“like putting a bin liner on the baby”). Other stories evoked how tots negatively experienced feeling like a baby, struggling with potty training and wanting to grow towards independence.

*“Design and Innovation through Storytelling” by Sara L. Beckman and Michael Barry reprinted from International Journal of Innovation Science Volume 1 · Number 4 · December 2009

Phase 3: Develop

Inspirational stories that spark a new vision

This leads us to our inspirational stories. In the story world, a hero faces a conflict that they resolve successfully. The bigger the conflict, the bigger the hero, right? So let me suggest something: for any human being, struggling with managing your own bodily functions can be a conflict of epic proportions!

To answer the question of how to make a child feel like a big kid, they amped up the springboard story** to match the pure emotional intensity of children. They told simple stories of how and when children felt like bigger kids, proud, like heroes in their own world.

“Sarah was so proud when she went on the pot by herself for the first time!”

Wouldn’t it be great if we could do that for kids who weren’t quite there yet?

The answer: develop a whole new type of nappy that kids could put on and remove themselves. Every time they did that, they were proving they could do something by themselves. The emotional connection was huge, much bigger than having a pink or blue coloured nappy.

**”The Springboard: How Storytelling Ignites Action in Knowledge-Era Organizations” by Steve Denning, Butterworth Heinemann October 2000

Phase 4: Deliver

Agile user stories as inspiration for solutions

At a high level, journey maps are a series of micro stories told visually. While they can be used to correct pain points, they are important for bigger ideation where you can focus on customer needs and intentions and try to come up with completely different ways to fulfill the need or intention. You can illustrate how a completely different idea would really work, at least on paper.

The last phase of the design process is delivery. Most UX and digital designers are familiar with Scrum methodology, where Agile user stories define slices of functionality to be built. Instead of writing system-based features and requirements, business stakeholders express processes and functionality as microstories.

“As a user, I want to [do something] so that [I get a benefit].”

IT teams then work in short sprints to make that specific thing happen. This is much better for an iterative design and development process as you can focus on delivering a result without being prescriptive about the solution.

Inspirational stories that become pitches

Once you have a functioning business pilot or digital prototype, you may have to create pitch stories that inspire stakeholders or customers to initially support a concept or adopt and engage with a developed solution. However, pitching is a real art. Telling your story effectively inside and outside your organization can make the difference between success and failure of your initiative.

The Hollywood pitch is often caricaturized as absurd, incoherent and improvised, like in this scene from Altman’s classic film The Player.

“It’s a psychic-cynical-political-thriller-comedy, but with a heart.”

While our fast-moving business environments are very similar to the brutally short attention spans in the film, good business pitches are concise, well designed and well practiced.

In a popular Medium post, a former Zuora exec provides a well-documented example of a constructed pitch. It’s actually very similar to the SPIF pitch that Gartner’s Gene Alvarez taught me while I was there.

SPIF = Situation, Position/Proposal, Implications, Future

For example, the SPIF for a ride-hailing app could be:

As most city-dwellers today expect everything to come to them (S), our platform helps drivers find riders (P) so that people don’t have to wait in the street anymore to find a taxi (I) – they just have to download the app (F).

If you work in a larger organization, think of how many great ideas that could take off much quicker they had a compelling pitch story:

Weak pitch:

Big Boss: What’s Project Sandwich?

Manager: It’s a cloud-based content management and distribution platform for the PDFs that our Research department publishes. The UI is a front-end native app which would replace the current repository and email distribution processes.

Big Boss: Uh…OK. Sounds good.

Better pitch:

Big Boss: What’s Project Sandwich?

Manager: Less than 10% of our clients have direct access to our research (S), so we want to build an beautiful magazine-style app (P) so that they can read customized content on their phones (I)…we just need approval and funding to make it happen (F).

Big Boss: Less than 10%? That’s crazy. How much are you asking for?

______

As we saw in the previous post, storytelling is inherently human, and much of the design and business transformation process is about understanding and influencing human behaviour. Storytelling is incredibly important to the overall business of design and the design of business.

The most important takeaway is that using stories in the design process is a discipline requiring structure, skill and practice. Gather informative stories in the beginning of the design process to drive insights and problem reframing and create inspirational stories at the back of the process to drive innovation and adoption, and your initiative will be more likely to reach a happy end.

One reply on “How Designers and Innovators Use Storytelling”

Great Thoughts on Story Telling as its the most powerful way to put any idea in the world and our brain retains what we listen to more than just listening to only facts.

LikeLike